We trace the 250-year history and the seven generations that have shaped the House of Creed – from tailor’s repair shop to dressing empresses, from scenting gloves to creating fragrances that sell in their millions.

All families have two histories – one passed down through the generations, the other a matter of public record – and the Creeds are no different. In his 1960 memoir ‘Maid to Measure’, Charles Creed – a serious player in London’s post-war fashion scene – describes the origins of the House of Creed. ‘My great-great-great-grandfather James Creed came to London from Leicester in 1710. He was a tailor, gifted and ambitious, and I dare say his fingers itched, like any good tailor’s, for the feel of rich stuffs which only “the quality” could then afford. But though I’ve no doubt he was an artist, I’m sure he had no wish to practice his art for art’s sake. The citizens of Leicester must have been the worst of payers: he was practically penniless when he set out for London.

In Charles’ telling of the story, James has a son, Henry, who follows his father into the trade, helping to build a thriving business from its outset as a repair shop for City gentry to creating outfits for London’s smart set.

Indeed, royalty and celebrity are regularly quoted in relation to the Creeds, possibly stemming from the oft-repeated story that, in 1781, James was commissioned by King George III to make a bespoke pair of scented gloves.

Years before George III’s granddaughter Queen Victoria took the title of empress, France had one of its own, who not only belonged on the world stage but also stole the style show. The daughter of a Spanish noble, Eugenie married Napoleon’s nephew. She became Europe’s most famous consort, renowned for her beauty and her theatrical style which included plumes of bespoke perfume gently floating around her couture garments.

Few 19th-century scenes could have been as theatrical as Eugenie’s arrival in Port Said for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 – a great moment too for Creed, propelling it forward in the minds of the fashionistas of the time. Wearing a cream yachting dress of lightweight serge made by her tailor Henry Creed – and reportedly laced with a delicate perfume – Empress Eugenie set off aboard the imperial yacht, with a flotilla of European royalty in her wake. The transit of the canal was a triumph – and so was the dress.

News of Eugénie’s stunning Creed dress spread far and wide, and by the 1870s, the name Henry Creed was known to most of the remaining royal courts of Europe, which were commissioning outfits from him as well as rewarding him with royal warrants. His patrons were no doubt also spritzing their tailored leather and hemlines with bespoke perfumes from their trusted tailor as was the fashion of the time, permeating their social gatherings with beautiful scents.

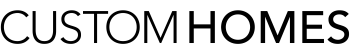

Clockwise from top left: Henry Creed; Alexandra, Princess of Wales sits side-saddle; Empress Eugenie’s son Louis-Napoleon (1874); Yum Yum (1886), young woman in riding habit by Edouard Frederic Wilhelm Richter; Empress Eugenie (1853) by Franz Xaver Winterhalter; London’s Conduit Street in the 1800s, site of Creed’s first shop; George III and the Prince of Wales’ Reviewing Troops (1798) by William Beechey; James Creed; Bulgarian rose, a key ingredient in Creed’s Fleurs de Bulgaria, created for Queen Vitoria; Henry Creed; centre: Count d’Orsay; late- 18th century gloves; Images Alamy/ Topfoto/Creed

One French aristocrat who frequented Henry’s London shop was the leading dandy of the day, Count d’Orsay, who wore six pairs of bespoke, extravagantly scented gloves each day, made by his English tailors including Creed. ‘D’Orsay wore clothes splendidly,’ writes Charles Creed in his memoir, ‘and whither he went the beau-monde followed. They followed him to Henry Creed.’

A deeper delve into the bulging archives reveals that under the patronage of Empress Eugénie, Henry moved the business to Paris in the mid-1850s to service his burgeoning high-society clientele there, and ever since there has always been an eclectic sense of both British and French culture and emotion infused in the Creed business.

By then, through its couture designs, Creed had become a worldwide pioneer of women’s liberation, introducing men’s tailoring to women’s wardrobes with their bespoke riding habits.

This helped pave the way for generations of women to feel comfortable in trousers – a critical contribution to the empowerment of women.

image: @cunningtonandsanderson

The royal commissions came rolling in. As early as 1860, an advert in The Army and Navy Gazette cites the tailors being ‘by special appointment to Queen Victoria and the Principal Courts of Europe’, referring to the fact that Henry and a team of 20 craftsmen would travel around the royal courts for consultations and fittings. However, it wasn’t until 1885 that Queen Victoria granted Creed a royal warrant, as a result of the bespoke riding habits he made for her.

Shot and injured in Paris in 1871 in the unrest following the collapse of France’s Second Empire, a heroic Henry returned to England. No doubt he felt safer on these shores, but he had always returned to London for the census which guaranteed his British nationality.

In fact, notwithstanding all their success in France, Henry and his sons always saw themselves as Englishmen first and foremost. Even today, his grandson Olivier travels on a British passport, despite living most of his life in France.

The 1881 UK census lists the Creed family as living in Hampstead, a leafy suburb of London, the firm at Conduit Street, and Henry as a master tailor employing 21 men. Lovers of sport and exploring, the Creeds were founding members of the Stanley Bicycle Club, one of the first of its kind, and this no doubt came in handy for the daily commute to the workshop in Mayfair. Around this time, Henry made a number of visits to North America, where advertisements for his clothes start to appear in newspapers.

A visiting card from 1902 gives two addresses for Henry Creed, by now both in France – 25 Rue de la Paix in Paris and 12 Avenue Massena, Nice. The House of Creed in Paris – now being run by Henry’s son, Henry junior – is as busy as ever. But why set up shop in Nice? By the early 20th century, the French Riviera was the place to be and be seen, with no shortage of well-heeled clients for a smart Parisian ladies’ outfitter with English tailoring credentials. Nice is also just 25km from Grasse. Once home to glove-making, specifically perfumed gloves, by this time Grasse was rapidly becoming the centre of France’s fragrance industry. Since the 18th century, from spring onwards, the fields around Grasse have been heavy with the scent of flowers – lavender, mimosa and rose among them – grown for perfumery.

Although in Victorian England women didn’t wear a lot of scent, fragrances were as much a part of their beauty regime as hair- and skincare, and were in demand. The scents, mostly florals and other botanicals, however, weren’t applied directly to the skin.

By the 1900s, simple, single-ingredient perfumes began to give way to scents made of many different extracts blended by an expert nose. And, with that, the perfumer was born, the modern industry took off and Grasse became its undisputed capital.

Meanwhile, on France’s Atlantic coast, in fashionable Biarritz, Coco Chanel opened a boutique in 1915 and, within a decade, had launched her first perfume. Undoubtedly in Nice and Paris, bottles of fragrance began to find their way into Henry Creed’s shops too. In 1913, Henry senior died, and his son Henry ran the company with his son James from Paris again. Before the First World War, women flocked to Creed to be fitted for their bespoke suits.

Moving to larger premises at No.4 Rue Royale in Paris in 1926, Henry Creed had truly arrived; next door was Molyneux, another English fashion and fragrance firm, and at No.14, Yteb, whose Art Deco adverts promoted their fragrances. Now it was time for Charles to see the world. Encouraged by his father, his first stop was glorious Vienna to learn the tailoring trade. Next on the adventure was Linton Tweeds in northern England, to serve as an apprentice – the very same place that Coco Chanel was sourcing her fabrics from and an inspiration for Creed’s world-famous Green Irish Tweed fragrance. Next stop, New York, where Charles worked as a floor-walker at Bergdorf Goodman at a time when it was quite unusual to find a Parisian-Brit working in the States. After all these adventures, Charles finally joined the family firm in 1935.

Meanwhile, in 1934, Henry’s other son James headed off on his own Grand Tour. Sailing first-class to the Far East, he toured Japan. There, a rich culture of botanicals existed that informed everything from tea ceremonies to cherry blossom festivals, which was eagerly devoured by well-heeled western tourists and our very own James Creed. As early as 1897, Japanese beauty firm Shiseido was selling rose scents. For the young man from Nice, it must have been an inspiring experience.

Back in Paris, Charles brought his experience and entrepreneurial instincts to the business together with those of his brother James to grow the Creed luxury brand, which was already well known to tastemakers in Europe and America. Having taken a ready-to-wear collection to New York in 1935 – the first Parisian outfitter to do so – Charles then, arguably, became the designer.

It was Creed that created the cult of the ‘label’, by sewing one into their jacket linings specifically so it could be seen. Charles also bravely suggested to his father that they set aside a department to sell gloves, bags and belts, sewn with his own special Creed stitch – the beginnings of the first boutique.

By 1939, the House of Creed was flourishing, and Charles writes that his womenswear collection enjoyed record sales in the US that year. In 1940 The New York Times reported that only two of the great Parisian fashion houses remained open: Lanvin and the House of Creed. Despite the war, somehow business carried on in England under Charles’ watchful gaze. In Country Life magazine, fashion editors wrote approvingly of charming Creed-designed clothes’in 1941 and again in 1944 sang the praises of a Creed winter coat – the highest accolade at that time.

Meanwhile, James had married and started a family in Nice – close to the famous lavender fields – and his son Olivier was born in the Italian-occupied city in 1943. After the war, Charles returned to Paris before deciding to go it alone in London, where he had made useful wartime contacts including Hardy Amies.

The London business flourished and Charles became a fixture in the capital’s fashion scene and a founder of the British Fashion Council. London’s fashion status to this day owes its reputation in part to Creed and his contemporaries.

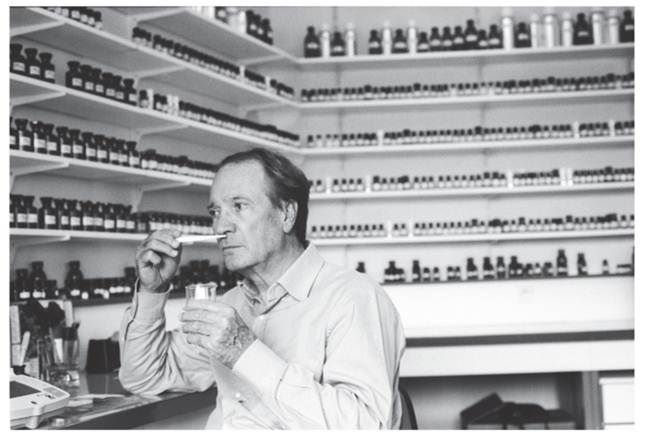

At the tail end of 1949, Henry senior died, and with him the last link to the Belle Époque. But, ‘from father to son’, as is seen on the bottles today, Creed carried on, first with James at the helm, and then, from 1985, Olivier. It was Olivier who transformed the fragrance business from around only a thousand bottles a year to the luxury recognisable flacons sold today.

Olivier Creed

The spirit of from father to son’ continues, as Erwin, Olivier’s son, brings his experience and point of view to the brand. Perfume is quite literally in his blood and, just like all of the Creeds before him, he adds his own flair and artistry while building on the successes and lessons from the past. Explorers and adventurers through the centuries, Erwin is no different.

One of Erwin’s many passions is racing driving. He takes part in races around the world and is an incredibly accomplished driver. It acts as a great antidote to the painstaking perfume-making in the rolling fields of Fontainebleau. Always looking to future opportunities, Erwin recognises the courage and pioneering nature of his ancestors – ‘our creations are a journey through time because the past is the strength of our future’.

One of Olivier’s many creations, Aventus, is a fragrant homage to Napoleon Bonaparte, who reportedly doused himself in whole flacons of scent. As you open a bottle of Aventus and savour its fruity head notes and spicy, woody base, it’s not inconceivable that there will be echoes of that other Napoleon whose glamorous wife Eugénie helped transform the fortunes of a London tailor. It’s a tantalising thought that perhaps, in her final years on the Riviera, the dowager empress had summoned her old tailor from his shop in Nice to travel the few miles to her villa. Did he arrive for a fitting with a new fragrance to scent her gloves and the silk linings of his latest creation? And if so, might they have gazed across the sea and recalled the twill yachting outfit he’d made for her voyage to Suez, when the world looked very different and destiny had yet to declare that fortunes must change?

Purchase Creed’s exquisite range of artisan perfumes at leading retailers and online at creedperfume.com.au